Russell Hoban the Illustrator

Click on thumbnails in this article to pop-up larger images.

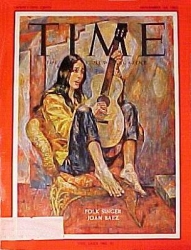

According to excerpts from the artist’s 1962 diary, Russell Hoban’s portrait of the folk singer and 1960s icon Joan Baez took 16 days from commission date to completion and delivery, and he spent around 10 of those days working on the portrait, with at least one all-nighter required to finish the job. Baez, sadly, was unimpressed. David Hajdu, in his book Positively Fourth Street (in which the painting isn’t reproduced), describes it as “an eerie Goya-style oil that could have been a thought projection of Joan’s distorted self-image … she is repellant – a skeletal ghoul clinging to a guitar…” Apparently Baez thought she looked “dreadful”, but the portrait perfectly captures the spirit of the times, and she doesn’t need the caption to be instantly recognised.

The Baez portrait was commissioned by Time editor Jim Keogh. Hoban’s recollections of the commission follow:

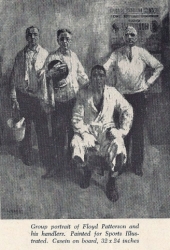

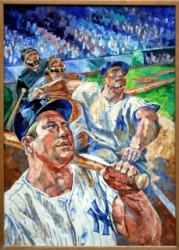

[Baez] was performing in Tucson, Arizona at the time so I flew to the nearest airport … She was with her current boyfriend who was not famous and whose name I don’t remember, and she was driving a sports car which she called her ‘little grey bomb’. I watched her at the Tucson venue and made sketches, then I followed her to Carmel, California where I did more sketching and observing. We had some kind of altercation, I seem to remember, after she had pissed me off about something. The painting was in an exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. last year. It’s owned by Time Inc. but I have the magazine cover which I keep meaning to send to Dave for The Head of Orpheus but I haven’t done it yet. The painting was done in my studio from my sketches and some photos Time sent me. Goya it ain’t. I also did a portrait of Jackie Gleason [pictured] which he didn’t like, a portrait of Maurice Richard of the Montreal Canadiens which was sent to me recently by a woman whose husband is a Sports Illustrated fan. She gave him an S.I. cover for every year since 1960 which is when they got married. Also did portraits of Jack Nicklaus and a double one of Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle [see small reproduction below]. These weren’t used as the cover stories changed.

For a time (he wrote in a February 2004 message on The Kraken, the Yahoo fan group devoted to his work), Hoban worked as an instructor on the Famous Artists’ School of Westport, Connecticut’s correspondence course, “where I used to do a tutorial sketch painting and a dictated letter”. The institution was founded by Harold von Schmidt with Bob Fawcett, Al Dorne and several others. “The school made a profit because of the correspondence-school phenomenon, that many people pay for complete courses they don’t finish,” Hoban wrote in the same message.

In the October 1961 issue of the magazine American Artist, designer, painter and author Frederic Whitaker interviewed Hoban for a feature article. Whitaker had an unusual, prolix writing style and something of an axe to grind about the emerging generation of younger artists (in which Hoban fortunately wasn’t included – he was already 36 by the time of that article). He does, however, provide some early biographical information that isn’t widely published elsewhere; for example, the fact that Hoban worked “exclusively in casein”, popular until the advent of acrylic colours, due to his allergy to turpentine.

Apart from his occasionally prejudiced turn of phrase, Whitaker’s is a thorough article of a kind rarely found in today’s magazines. At one point, in describing Hoban’s drive in tough economic straits, Whitaker writes:

Hoban has the analytical ability and the tenacity of a veteran mail order executive.

I’m not sure that’s a compliment. The article includes this telling quote from the artist:

I wanted no part of an educational package. I was sure I could learn by reading and observation all the schools could teach me, and also a good deal more of my own choosing.

And it also contains some fascinating nuggets about early inspiration and Hoban’s self-taught powers of observation that he would be able to put to such good use later:

From the age of five he drew incessantly from everything in sight. He even sketched at the movies. He was particularly fond of horses and drew them from life at every opportunity. During his teens he studied horse anatomy and spent long periods in a stable studying all manner of details, even such unusual subjects as the bolts, springs, steps, and other parts of carriages as viewed from the floor.

Hoban’s early work experiences following the Second World War have rarely been described in such detail:

He was successively freight handler, shipping clerk, Western Union messenger, electroplating assistant. During the evening he began free-lancing as a designer for silk screen shops. Art work developed into daytime employment with small magazines, first in production and later as an illustrator. For six months he was art director for Printers’ Ink, where he learned much about printing and reproduction. He served two years as an illustrator with the Wexton Company, an art studio. Meanwhile he learned that good money was available for drawing story boards. To those unfamiliar with advertising parlance, these are the preliminary crayon sketches in panel form used for rehearsals of a television commercial…

Whitaker’s article also describes how Hoban applied to large New York advertising firms, and got a positive response from BBD&O:

He offered to set up a television production department, but instead the firm gave him free-lance work and later hired him as an assistant director in television production. Note that with all this experience, including three years in the Army, at this point he was only twenty-five. He remained with B.B.D.&O. five years…

Sporting life

After a spell working in films and doing no painting, Whitaker writes, Hoban made the decision to use all of his spare time for painting:

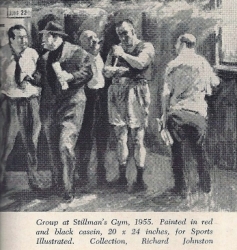

He assumed that in New York every artist paints the Fulton Fish Market, Washington Market and Stillman’s Gym (the training quarters for pugilists made famous by George Bellows), and he tried all three. But soon his luncheon hours were all spent at Stillman’s madly sketching his new boxing friends. He became particularly interested in and made a study of the necessarily varied natures of the fighters, the managers, and the trainers, who are usually superannuated pugilists.

One of Whitaker’s most fascinating insights is that Hoban himself once trained, non-professionally, as a boxer but dropped the sport due to poor eyesight.

The sports illustrating continued, however, as did Hoban’s association with Sports Illustrated: his 1960 portrait of the US athlete Rafer Johnson was one of a series for the publication that also included the golfer Arnold Palmer, heavyweight boxer Floyd Patterson and Olympic figure skating champion Carol Heiss. [Webmaster's note 3/5/14: Articles have since been discovered on the Sports Illustrated website in which Hoban writes evocatively about Floyd Patterson's world title and his portrait in March 1957 (with further comment on the article by "the Publisher"), comments on sketches he made of Toronto Maple Leafs hockey players in November 1956, and provides "enthusiastic word impressions" of an imaginary basketball team in December 1958. Sadly the illustrations themselves are not included.]

Poe, the night-writer

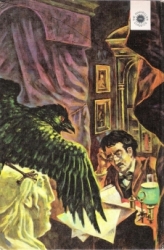

My personal favourites of the Hoban illustrations I’ve seen are those he provided for Tales and Poems of Edgar Allan Poe, which were published in Macmillan (New York)’s 1963 edition. The dust jacket copy reads:

With sweeping color and sharp-edged reality Russell Hoban’s illustrations are a brilliant and passionate mirror for Poe’s strange world of fact and fantasy.

Most of them were reproduced in colour in the Macmillan edition, but Elisa Bowman and I converted two to black and white for 80!, the Kraken book published by Bloomsbury to commemorate Russ’s 80th birthday in 2005. The Tell-Tale Heart illustration was on page 241. The Raven illustration was reproduced only on the book’s cover and dust jacket.

[Webmaster's note: all the Poe illustrations can be seen on this blog.]

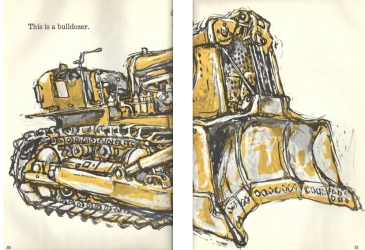

Girt big things

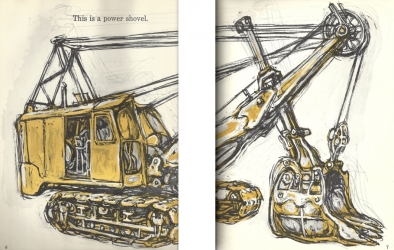

The children’s book What Does It Do And How Does It Work? has 29 double-spread illustrations (hence the binding margin in the images reproduced below) and features five machines – power shovel, dump truck, bulldozer, tractor shovel and motor scraper. The illustrations were scanned for me by Ben Hennessey at Red Kettle Theatre, which staged a production of Russ’s play Riddley Walker. Published in 1959 by Harper and Brothers, it’s dedicated to Phoebe, Abrom and Esmé and prefaced by a Walt Whitman quote: “…And there is no trade or employment but the young man following it may become a hero…”

I’m fond of his bulldozer and power shovel illustrations because they’re fluid, oddly organic, and call to my mind at least the “girt big thing” found in the digging at Widder’s Dump in Hoban’s classic novel Riddley Walker, the excavation of which did for Riddley’s Dad:

…some girt bit rottin iron thing some kind of machine it wer you cudnt tel what it wer.

The Atomic Submarine – A Practice Combat Patrol Under The Sea (published in 1960 by Harper and Brothers) has 14 illustrations in black, white and greys – two copied from a diagram and a photograph – and nine illustrations showing the crew.

Ben Hennessey writes:

I include one showing the cook in the galley; one with the captain and a crew man looking at the radar repeater; and one with the Captain and officers looking at their stopwatches in the attack centre…

In a review of What Does It Do And How Does It Work? the Virginia Kirkus’ Service said:

Written in a compellingly rhythmic prose and illustrated by the author in bold pictures reminiscent of Roualt’s paintings, this book dramatizes for the younger reader the force of the heavy machine and explains its function and mechanism.

Art continues to have an important place in Russell Hoban’s novels; in fact, you might say other artists’ paintings are among his characters. So it’s even more intriguing to wonder how his writing might have been enhanced and our perceptions of his books altered if he’d continued to make his illustrations public as Mervyn Peake did. As it is we have at least two careers to consider.

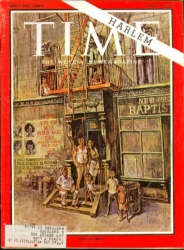

- Thanks are due to Yvonne Studer for providing a copy of Frederic Whitaker’s article about Hoban in American Artist magazine; to Ben Hennessey for supplying the scans from What Does It Do And How Does It Work? and The Atomic Submarine; to Olaf Schneider, who found the Time Harlem cover in a chance search on eBay; as well as to the other members of The Kraken who have shared Hoban’s illustrations over the years.

- If you have copies of any other Hoban illustrations, feel free to leave a comment below or to get in touch – maybe there’ll be a Part Two one day.

- This article was updated on 3 and 6 May 2014 by the webmaster to add links to Sports Illustrated images and articles, and on 28 June 2014 to update those links after SI broke them.

- Log in to post comments