Nutrition for the Eyes: An Interview with Russell Hoban from 1995

This interview took place at the author’s home in Fulham on September 28th, 1995. Hoban’s study – a veritable curiosity shop – reveals his wide interest in and knowledge of many subject matters. The room is lined wall to wall with books – on lupine mythology, religion, zen mysticism, archaeology, art history, Haiku and anthropology. There are videos – of films such as King Kong, Dracula, Terminator, Mike Leigh’s Naked and Kieslowski’s Three Colour series, and CDs – of Albert Collins, Hawkwind, J.S. Bach, and Jan Garbarek, and numerous artefacts – masks, dragon puppets, kites, maps, a print of Vermeer’s Head of a Girl, and also the figurines that inspired some of his best known books – the mouse and child clockwork toy, and the frog and the night watchman from the La Corona and the Tin Frog collection.

Now 71, Hoban shows no sign of relaxing his work schedules. He has the passion, verve and vivacity of a man half his years, and a voracious appetite for knowledge and learning; moreover, he embraces all cultural forms without discrimination. This interview bears testament to the fact that he is as comfortable and as informed when discussing contemporary European cinema as he is twentieth century literature or modern popular music. Hoban was most hospitable and accommodating, frequently humorous, and always fully prepared to discuss any aspect of his life – his viewpoints, his philosophies, his work and even his disappointments.

The initial focus for conversation was the issue of adapting novels into films: The Mouse and his Child has been produced as an animated film, and Turtle Diary as a feature film (screenplay by Harold Pinter), starring Ben Kingsley and Glenda Jackson; also, Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas was adapted by Jim Henson, and Hoban has collaborated with contemporary British animator David Anderson, on a film entitled Deadtime Stories for Big Folk.

The author’s most recent works include the libretto for the opera The Second Mrs. Kong (music by Harrison Birtwistle), an adult novel – Fremder, The Trokeville Way – a teenage/adult novella, the children’s books Monster Film and The Court of the Winged Serpent, and a collection of poetry for younger readers, The Last of The Wallendas. Awaiting publication is a new adult novel, Mr. Rinyo-Clacton’s Offer – which was in part inspired by Kieslowski’s Three Colours White, a film that Hoban discusses in this interview.

The interview veered off at many unexpected tangents, with Hoban reading from the works of the Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola, and playing the music that he enjoys – the music that acts as a focus and an inspiration for his writing. Hoban also spoke fondly of the Bulmershe campus at Reading University (where I was doing my MA in Children’s Literature), which he has visited on a number of occasions to give talks and creative writing workshops. The tone of the interview was at times jovial and light-hearted, and I hope that this element translates into this text. I am most grateful to Hoban for his warm hospitality, his willingness to talk openly and candidly, and for his assistance with the production and revision of this transcript.

JC: Roland Barthes has referred to the ‘plurality of the text’. Do you believe that novels can possibly offer more potential meanings than films?

RH: Not necessarily. I, for example, am at the time in my intake when I read very little, and I watch a lot of videos, a lot of films that I tape off the TV. And I think you can have just as many layers and levels in a film that you can in a novel. I do think that of all the arts, writing is the most primary and the primal one, even more than the visual art. And maybe, drawings on the walls of caves came before writing, but writing is what, in itself, can give you more of the other arts. It can do everything: it can convey information, give you emotion, excitement, thrills, everything.

It is estimated that 75% of films are adaptations of novels. Why do believe this figure to be so high?

It’s a very simple answer: that film makers are always hungry for stories. And so, a book gives you a story that’s been fully realised, and if it looks like a good story, maybe they think they can do a film of it. But more and more, as with Kieslowski, I think the best films are written as films. Recently, I’ve become much interested in Kieslowski. I’ve now seen all three of the Three Colours, and I’m going to watch them again.

Which of those was your favourite?

White. And my son Wieland has watched it, and I think White is his favourite too. But what is instructive to me in those – apart from them being brilliant cinema – just as nutrition for the eyes – you can’t beat them, they’re just so juicy to look at.

Why do you prefer Three Colours White?

Well, more than in Blue and in Red, in White, I could see his approach at its most successful, and what his approach is – is to take people who are either in themselves strange, or at a strange time in their lives, and they meet other people who are in themselves strange or at a strange time in their lives, and strange events result from this. Each event generates another interesting event and always you want to know what’s going to happen next – it’s the essence of story – it’s something I should do more of.

Nabokov once stated that a film should be a ‘vivacious variant’ of the original source material. What is your perception?

Well, I think the most successful film translation I’ve seen is that of The Leopard by Lampedusa, with Burt Lancaster – and I think – Claudia Cardinale, Alain Delon. He may only have written that one novel, I think. He was an Italian aristocrat, and the book is very elegantly written. The film was done with great care, so that many of the visuals look like period paintings – with great attention to such things as a groom looking after a horse – rubbing it down with straw, and the horse is the right kind of horse, and the groom looks right and the stable looks right. The period was captured perfectly. And also, the essence of the film, what it was to be – not that I know – but it felt as if what it was to be of that kind of a family at that time was very well conveyed. A beautiful film. I’ve seen one or two films that were better than the book, and I’ll never forget whatsitsname – I can’t remember the film I’m thinking of, that was better than the book!

Do you think that’s rare?

It’s rare in my experience. You know, I’ve seen all kinds of failures – from Moby Dick to Lord Jim, both of which were embarrassing. The thing about the very best books, I think, like Conrad’s Nostromo, is that for one thing, the life of the book continues in your mind after you’ve finished the story of the book. And there is something in the book itself which is beyond the writer’s grasp, and the ungraspability of it makes it continue its action in your mind.

A common sentiment attributed to a film that has been adapted from a novel is that “It’s not as good as the book”. Do you believe that this is partly due to the fact that a reader makes a novel their own property – by internalising, subjectivising and visualising the text – and hence a film version can rarely or never match a reader’s own realisation?

Yeah, I pretty much agree – but also, I think that it’s because the people who make films have enough sensitivity to respond to what’s in a book, but they lack the artistic intelligence to make the translation into film. They are not able to seize on what is the essence of the book. For example, with Turtle Diary, I think of it as my Haiku book, because the Haiku poems have to do with nicely observed detail always – at a time of day, at a time of year, and whether it’s the sound of the frog jumping into the old pond, or going out to watch the cherry blossoms, or moon-viewing, or views of Fuji, or whatever – but all that was lost. All of the detail that really was the solid foundation for the story – nobody bothered with.

They just took the skeleton of the plot.

Just the skeleton of the fairy story.

In the soundtrack to the animation of The Mouse and his Child, the protagonists are represented by a rhythm on a conga drum, the tramp by a melodic saxophone, and the rats by a ‘Trad’ jazz theme – what do these musical motifs signify for you?

I’ve no recollection at all of the soundtrack. I can’t really give you any specific comments about The Mouse and his Child, because I’ve seen it once, or twice, maybe just once, and it was just lamentable, it was a bad piece of work.

If you had to state a preference, which adaptation do you favour, Turtle Diary or The Mouse and his Child?

Well, Turtle Diary is better – it’s feeble and flabby compared to the book, but it doesn’t subvert the book as much as the animation feature does.

In what way do you believe that the animation of The Mouse and his Child subverts your original text?

Well, are you talking about the animation itself, or that film?

The animation.

The animation itself is completely undistinguished. It’s just a, sort of a general Disney-derived style. Now the book is not written in a general Disney-derived style. I would say if they had any artistic intelligence they would’ve tried for a style something like Arthur Rackham. Do you know his work it all? He was an illustrator. He died sometime in the nineteen-hundreds – I don’t know when. He illustrated – oh, all kinds of things – he did Peer Gynt, he illustrated various fairy tales. He had a very distinctive style, very – oh, full of strangeness and elegance, and all kinds of things. Now if they had had a look at him, they’d have been better off. And I made a bad choice with that film because I had an offer from David Niven – the actor who died some years ago – and he was into film production at that time, and he wanted to buy the rights to The Mouse and his Child. And he said that he had a whole town full of animators in Czechoslovakia, I think it was – somewhere in Eastern Europe – where they do a very high standard of animation, and they would have done it with tender loving care and all that. And maybe I just turned it down because it wasn’t enough money, I don’t remember why. I was sorry afterwards. Because the look of the thing is very down-market and, as I say, very undistinguished, and the look of it is as bad as the screenplay.

Are there any animated films that you particularly favour?

Yeah, there’s one very short one done by a Czechoslovakian animator called The Metal Horse. It’s too tiresome to go through the whole story for you. And then there’s another one, by a British animator, Alison De Vere, called The Black Dog. And then there’re others – The Brothers Quay – who do some marvellous things, and there are a number of East European and Russian animators who do real art. I mean, there’s no concessions made to lower standards, or making it accessible, they just do what they do, and they’re beautiful.

Because the strength of Turtle Diary is contained in your use of language and the metaphysical ideas that you raise, do you feel that, to capture an element of this in the film, the first-person voice-over convention could have been used?

Yes. That film could have done with a lot of visual content that it didn’t have, with voice-over. For example, with simple touches like, when William is walking home and he steps on a metal plate on the pavement, that says ‘K257’. He looks up the Köchel number and it’s the ‘Credo’ [-by Mozart]. That would have been a nice touch to the film that wasn’t there.

When reading the novel, I felt that not even a small percentage of it could be captured on film.

That’s right.

And I often find when reading your novels, they take me a while to read, as I have to frequently leave the text to ponder over the ideas that you raise.

But what I am, for better or worse, is a metaphysical writer. And my particular metaphysics don’t sell that well. I have a very small readership. And it’s the sort of thing, where as you say, you read reflectively, you can read a bit and think about it.

In which country do you sell best in?

[-laughs:] I don’t know! I never look at my royalty statements that carefully! I think I sell better, proportionally, here, than I do in the States. I sort of manage to fall between the two stools – the Brits tend to think of me as an American, and the Americans tend to think of me as a Brit – so, nobody gives a damn!

In your article entitled Thoughts on a shirtless cyclist…. you stated that ‘books in nameless categories are needed – books for children and adults together, books that can stand in the middle of an existential nowhere and find reference points.’ Which of your texts – other than The Mouse and his Child - would you place in a ‘nameless category’?

Well, I have a new book coming out in May next year, called The Trokeville Way, and that’s one like that.

What age group could it be appreciated by?

Well, it could be appreciated by 12 on up. It deals with the situation of a boy just before puberty, and the nature of it is such that it would interest adults as well as boys and girls of that age.

Critics favour the term ‘Hobanesque’ when discussing your work. What does this term mean for you? What do you perceive to be your idiosyncratic qualities as a writer?

Oh, I don’t know, that’s for others to say. I’m a metaphysical writer, and I do it how I can. That’s all I can say! I take hold of whatever offers itself as a way of saying what seems to me to want to be said.

To find the right form for whatever your ideas are?

Yeah. I’m an endless reviser, I’m always trying to get the thing in the shape it wants to be in.

How about when a work has been published, have you ever wanted to go back and do another version?

No, I’m pretty – what shall I say – grown up about that, I simply accept the fact that what I did was the best I could do at the time. And I don’t let go of the thing until it lets go of me. Riddley Walker took me five and a half years, and other books might take two years or one year, but I don’t call them finished until they have absolutely relaxed their jaws and dropped me.

It often seems to me as if your children’s books are a by-product of your adult titles, or that they stem from the same set of ideas that you have.

Oh yeah, everything comes from the same place, some [-ideas] can be put in a smaller form and some can be put in a bigger form, and some can be contained within a child’s frame of reference, and some not. But yeah, it all comes from the same place.

Am I right in assuming that you are the tramp in The Mouse and his Child – an outsider, an omniscient figure that empowers the protagonists and allows them forwards motion, in order that you can observe their destiny – and by stating ‘be tramps’ you are encouraging them not to conform to their expected roles and to discover the possible boundaries of their existence?

Oh, I don’t know, I suppose I’m all the characters in the books I write. I simply thought of the tramp as the force that gets them moving and encourages them to keep moving.

Will the sequel to The Mouse and his Child – The Return of Manny Rat ever surface?

It’s not likely – that got lost in my passage from the U.S. to the U.K. – that was transitional between my writing about anthropomorphic animals and toys to writing about men and women in my own thoughts and experience. Once I felt free to do the latter, I gave up the former. I didn’t give it up, but I left The Return of Manny Rat unfinished. [Webmaster note: a fragment of the story was later published in A Russell Hoban Omnibus (1999).]

[At this stage, Hoban takes the original model of the mouse and child. He places them onto a wooden board and winds them up and they dance in a circular motion. Webmaster note: You can see this for yourself on this YouTube video.]

Didn’t I say in the foreword or afterword that it was part of a collection of clockwork toys that friends had under their Christmas tree? And I watched it for about three years. And I found I had to write something about it. I thought it might be a step up from the Frances texts, thirty-two pages, or something like that, or a somewhat longer story. I had a very good editor at Harper then – his name was Ferd Monjo – and he was very good at teaching me to explore my material, and I’m still working to rules I learned from him.

How much do editors play a part in your work now?

It’s less and less, but with my new book, with The Trokeville Way, I had some very useful comments from an American editor.

How did you map out/plan the narrative to The Mouse and his Child during the writing process?

The writing of it was the longest I’d been on anything – well, up until then I’d only done picture book texts – and this was my first novel. We lived in a house with a very big living room then. I think it was something like twenty eight feet wide – a big, open space. And I used to lay out my pages on the floor and walk up and down the width of the room trying to get the whole story so far in my head and see if it was organised properly. I did a number of revisions, and I made some notes, I talked with my editor whom I’ve already mentioned, Ferd Monjo. It took me about three years to get it together, and much of the time was spent in the organisation of it. Although part of it was in getting from the first not very good draft to the last one. And that I’m very indebted to Ferd on that because some of my first efforts were abysmal.

Presumably you were writing by hand at that point?

No, usually typewriter, and I would write by hand for a while and then type out some pages. That was how I used to do it when I worked with a typewriter.

And now you do it all on the word processor, and you don’t write manually at all?

No, because I can change it constantly as I go. Sometimes I stop and do some manual writing, and make some notes.

Do you think that there is a very different kind of process when you use the pen as opposed to the keyboard?

There is. It’s very difficult to explain what it is. Recently, I did a words and music programme with Anthony Rooley, and I did some – it was sort of a blank verse thing about the music of William Lawes. And I found that I wanted to write those out by hand. And when I’m doing poems I always write them out by hand.

Is it more organic, do you think?

Oh yes, it’s more organic. And often when I’m stuck on a novel and making notes to myself I do that by hand.

Jan Mark once commented that you are a philosopher, not a children’s writer. How do you respond to this?

[-laughs] I’ve no response to that!

Why did you decide to have Neaera H. as a children’s writer/illustrator of anthropomorphic tales in Turtle Diary?

Well, I’m often limited in my novels by my own first-hand experience. There are times when I might’ve made Neaera a police pathologist, if it hadn’t required too much research!

But Neaera had to have had that type of occupation for her to be in tune with the themes you were addressing, or it would have been a completely different kind of novel otherwise.

Yeah, it would have been a completely different kind of frame of reference, she wouldn’t have been that kind of a person, but she would have expressed it in different ways.

Were you consciously reflecting upon your own motivations as a children’s writer?

Not so much my own motivations, as going through the situation of being a children’s book writer, and how is it that I could make money from it, why did people want to buy that sort of thing. My most successful books are the Frances books. They outsell anything I’ve ever done, and they continually go into new editions, and new book packages, and they’re used educationally, and they’ve had favourable reviews from child behaviour institutes and experts and all that, and I think it’s because everybody seems to like the idea of a world in which problems can be solved if one pays enough attention, and cares enough, and everything can be made to come out all right.

In a moral universe.

Yeah. That’s the world that’s presented in the Frances books.

How do you feel about that? Are you annoyed that all of the work that you have done since Frances has not sold as well?

Yeah, I am. It’s a tough business being a writer. A lot of writers can’t make a living from it at all, so I’m lucky that I can make a living from writing.

And that you can write the Pilgermanns and Riddley Walkers because of the Frances books!

Yeah, that’s right – but it’s not quite that simple – Riddley Walker and Pilgermann brought in larger advances than I ever got for the Frances books, and I continue to be able to support a family on my writing because I have enough things going across the board. There’s always money coming in from something.

How close is the sentiment below from Neaera H. in Turtle Diary to your own on writing for children, and do you believe that we write for children primarily to perpetuate our value systems and visions of how society should be :

‘People write books for children and other people write about the books written for children but I don’t think it’s for the children at all. I think that all the people who worry so much about the children are worrying about themselves, about keeping their world together and getting the children to help them do it…’ ?

I think a lot of writing for children is done that way, certainly there are exceptions. I haven’t read any of Roald Dahl’s children’s books, but those are anti-establishment books, I believe. But in general – no, I’m not informed enough to say ‘in general’ – all that I know is that, of my children’s books, the little, cautionary, moral tales like the Frances stories, are the ones that do best.

In certain respects, it seems that with your novels such as The Lion of Boaz Jachin and Jachin Boaz and Turtle Diary that there is, in a sense, more subtext than text itself, and that if you were to write a piece on the themes that you are addressing it would be of greater length than these novels. Do you still make notes on the ideas that you address in your narratives – what you have termed ‘philosophical vapourings’ – during the writing process?

Yes, I do. I usually have notebooks going with bits that may find a place to live in, at a future time – sometimes just a single line, a thought that seems to matter to me.

In Meet The Authors and Illustrators you comment that:

‘People say that every artist has a particular theme which he goes through over and over again, and I suppose mine has to do with placing the self – finding a place – and in one way or another most of my characters in my books go through it.’

What other elements of your own personal history are appropriated into your work?

Well, usually in my novels the protagonist is jolted out of – or breaks out of –one mode of living and is forced into or presumes another mode of living. My life’s divided itself into two parts: my life back in the U.S. and my life here. And so most of what I write about has to do with someone going through a radical change in life.

Has writing been your own form of ‘self-winding’?

Yes. The word ‘fulfilling’ gets thrown around a lot. I feel most myself when I’m writing, and when I haven’t got a novel underway, or some kind of a big project under way, I feel like a hermit crab without a shell.

At the ‘Still There Will Be Stories’ conference at The Royal College of Art, you made a comment about receiving catalogues from publishers advertising teenage books that deal with the issue of drugs. Do you believe that such matters as narcotics should not be addressed in children’s literature?

I was annoyed because books are written for market slots and I suppose my remark was unjust in that there must be worthwhile books that contribute to understanding the problems that make children take drugs, but they don’t usually result in literature, I think.

Please explain your fascination for Wilde’s A House of Pomegranates.

I read it as a child, I must have been eight years old. We had a room called ‘The Library’, and nobody I knew had a room called ‘The Library’ – it was a room full of bookshelves and books and a big table etc. And, running my eye along the shelves one time, I saw this small orange book with Oscar Wilde’s signature imprinted in black on the cover and I opened it. It was like opening the door on more world than I’d experienced before, that book was a – I don’t think it’s too much to say it was a life-changing book – because there suddenly rushed in upon me the richness of language, and the marvels that could be wrought with words. And I’ve never outgrown those stories, the ideas and the feelings in them have stayed with me, and have stayed valid ever since.

What other writers have directly affected you?

I can’t see any stylistic influences, there are writers who have made me internalise certain standards – Joseph Conrad, for the way he controls your access to the heart of the matter, and I’ve never achieved the technical mastery that he has that way, where he keeps you circling round and round the thing until finally he lets you have a glimpse of it. And Dickens, just for the pure energy, and narrative zest, and joy of words.

Do you ever find that as you are writing you are being indirectly influenced by what you have recently read?

That’s one of the reasons why I almost entirely avoid contemporary fiction, because sometimes I’ll pick up a book and I’m just made to feel so inferior, I feel this guy’s so much better than I am, that why do I bother? Other times, I find that a certain way of writing is so beguiling that it seems like the only way to write. For example – you say your reading hasn’t been as extensive as it ought to have been – maybe you haven’t read a book called The Palm Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola, he’s Nigerian, I think. He writes in this wonderful, strange English, these very strange stories. It’s such a magical, natural and organic way of writing, you think: “Why have I ever written any other way? Why doesn’t everybody write this way?”

Are you saying that he isn’t too bound by conventions?

No, no, he is bound by some kind of convention. I can read you an extract. [Hoban reads an extract from ‘The Complete Gentleman’ taken from The Palm Wine Drinkard p.222]

Why don’t I write like that?!? [laughs] It’s so delightful! You can say whatever you need to say, you can include everything, you can say, you know, “The gentleman was wearing striped trousers and also had a dream in his head of a Zeppelin” or anything at all, and it works, you know, it’s a very comprehensive way of writing.

Throughout all of your work, you display a tendency – almost self- deprecatingly, to suggest and promote ideas, yet you never dogmatize, or provide a conclusive Q.E.D. for your theories. Perennial terminologies for you are ‘thing’ ‘sort of thing’ and ‘thingness’. Do you believe that what you are addressing are spiritual and metaphysical ideas that cannot be given definitive labels or statements?

I guess so – that’s not a very comprehensive answer [-laughs] – I guess so! I don’t have any pretensions to being in possession of big answers, or big systems, I’m just feeling my way along, the best I can, and writing it how I think it is, how it seems to be. I can never do more than offer subjective reflections and perceptions.

What unique qualities or perceptions do you believe that an illustrator brings to novel writing?

Well, the way you put it, I think I’m sure there are – well, Conrad – there’s no better example than Joseph Conrad – of a tremendously visual writer, who as far as I know did not paint or draw at all, and he’s quoted as saying, “Above all, I want to make you see”, and he does it, as no-one else does it. He does make you see. So, I think that, my visual perceptions inform – my drawing, and my painting also – inform my writing.

Do you personally choose the illustrators for your children’s texts? What criteria did you apply for specific texts, say for example, The Marzipan Pig?

I’ve never had an illustrator forced down my throat. I always talk to the editors about illustration. With Marzipan Pig – well, Quentin Blake seems to me the best illustrator for a lot of my texts.

What quality does Quentin Blake bring to your work? Is it a sense of mischief?

Sense of mischief is the right word, a little bit of anarchy, a little bit of mischief.

How useful do you find music as a source of inspiration?

I always have music on. I got into the habit when we had neighbours who played loud music, and I would put headphones on, and immerse myself in my own music. I pretty well require it as insulation and as support. I find that, for example, some things are good energising music, like Jan Garbarek, a CD called Madar. He works with a lot of Indian musicians, and so forth, with tablas, with a very strong beat, and complicated rhythms, not like pumping heavy metal music. I’ll put on a bit, so you can hear what I’m talking about. [Hoban goes to his desk and puts on the aforementioned CD.]

Do specific pieces of music enhance certain moods, and do you find that you have to keep listening to those pieces when writing a certain book?

I found that when I was working on my most recent adult novel, which hasn’t come out yet, - it’s called Fremder – I had Bach’s Art Of Fugue on a good bit of the time, because that was talked about in the book, and also it had the flavour of it for me.

Is music fundamental to your work?

Absolutely. And, there are times when everything seems to be falling apart, and I’ll put on Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier, which gives me a sense of order in the universe, and this one, I find that often I like to start the day’s work with this one. [Webmaster note: see also the 1996 article by Hoban on his musical influences, 'Partly now, partly remembered', which contains links to some of the pieces mentioned above.]

What advice would you give to creative writing students? I’m currently running a course with some GCSE students; the course is more concerned with the concept of where ideas come from rather than concentrating upon form.

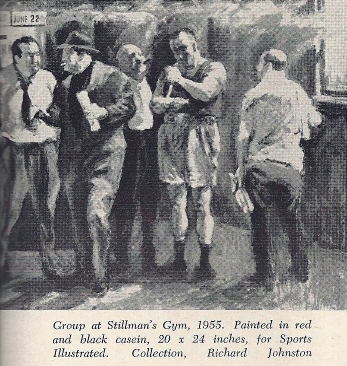

The advice I’d give them is probably what you’re saying already – don’t worry about the form, and don’t worry about beginnings, middles and endings, take hold of the thing, wherever you can, whatever of an idea presents itself to you, whether it’s the foot or the elbow, grab it, and work out from there. And the other thing is, don’t expect too much of yourself, but – just as people who are thrifty, and who save money – and don’t wait until they’ve got fifty pounds to put in the bank, but put in a pound, or five pounds, or ten pounds, and it accumulates that way, do something every day. If you can only write a paragraph, do a paragraph. If you can write a page, do a page. A whole story, okay, an idea, okay, notes, whatever – just get into the habit of doing something every day. And, let the ideas develop as they will – don’t require of yourself that you do a whole story or a whole novel, just do whatever you can – every day. I learned that method when I was becoming an illustrator. I had a full-time job at an ad agency, and I wanted to be a freelance illustrator, and I’d come home from work – I lived in Brooklyn at the time – and I’d made a studio for myself in the basement, and usually after supper I’d have a little nap, to gather some energy, and then I’d do whatever I could. I would try to do a sample illustration. Or a sketch, or anything, but I just did something every day. And at first, everything I did looked as if it came from a different hand, I didn’t have my own style, my own approach.

Were other styles coming through, from other people, that you had previously learnt?

Not so much other people that were coming through, but different aspects of myself. You wouldn’t have looked at all those things and said they came from the same hand. But one thing I found was that I was able to develop a technique by allying that development to a particular subject. Now it happened that I found Stillman’s Gym in New York City a very interesting subject. It was on 8th Avenue, and you went up these stairs that smelled of urine. And there were two rings, and the owner was a guy named Lou Stillman who always carried a gun. And there was a bar and lunch counter at one end, you could get beer and sandwiches, and so forth. And there was this little sub-culture of these triumvirates: the manager, and the trainer and the boxer. The boxer, he had his muscle and bone to sell. And the trainer was usually a used-up boxer, and the manager was often a hopeless idealist and self-deluder, who thought, you know, [-in parodying voice] “This time, I’ve really got a contender, I can feel it, I can feel it here, I’m almost sick with it, I know I’ve got somethin’, this time, really!” And, so I went there to make sketches of them, and I took photographs of them, and kept a file of various ones, and by trying to get better and better at my drawings, and paintings, of that subject, I developed my technique and my own approach. [Webmaster note: read more about this period in the article 'Russell Hoban the illustrator'.]

Do you ever visit schools to give readings and creative writing workshops?

The last workshop I did was for the Royal College Of Art, for the animation students. Their teacher wanted them to get some help with putting ideas into words, because she felt that they tried to rush into art too soon before they developed the ideas.

So you were trying to get the story aspect there, before they started to visualise it?

Yeah, the essence of the thing. In the workshop I used the film Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia as a model, in that it seemed to me, the screenwriter and the director – who I think collaborated on the screenplay – had not had a scheme of deep meanings in mind, but just working from intuition to intuition, they put together something that had many, many meanings beyond the immediate action, that had all kind of resonances.

That they possibly weren’t aware of?

That they weren’t trying for. I think that they intuited them, and they felt them, but you know there are some films where you see, oh, they worked out something in their heads, that is going to have heavy significance, and you could feel the cog wheels turning. In this one it just seemed to refer somehow to everything, and to have mythic qualities without trying for it. I was saying that all cognitions are re-cognitions. And the thing was to look for those elements in your story or in your film that would do that for the viewer, and that on seeing that, the viewer would say “That’s something I know.”

To act as a touchstone for something else for them?

That’s right.

Which of your texts – children’s and adult’s – would you most like to be remembered for?

It’s hard to say. Right now, I fancy The Trokeville Way as my favourite book for young readers, and I don’t really know about my adult books – I prefer different ones at different times.

Other authors have told me that they often take preference to their current pieces. Is this the same with you?

In my case, no. The current adult novel, which is Fremder – coming out in March here – is not my favourite adult novel. All I can say is that at different times I like different ones.

One word that crops up in your writing is ‘palimpsest’. It seems such a useful and logical way of considering history and geography.

That’s why I use it so much. One thing on top of another.

When I visit different places I often imagine the past rising up and through into the present.

I had that sensation very strongly when I was doing the research for Riddley Walker – at a place I visited in Kent. It was almost a little mountain, it was near Wye. I drove up this very steep ascent and parked at the top, and looked down on a little valley, where there was a very prosperous-looking farm, and below us there were crows soaring. And I had the feeling that who knows what raiders might have stood here, centuries ago, looking down on the farm they were about to plunder. And it seemed to me that I could feel this palimpsest of centuries rising up through the air of that little valley.

WORKS CITED

Texts –

Conrad, Joseph – Nostromo (Penguin, London, 1974)

Hoban, Russell – Frances series (Picture Puffins, London)

Hoban, Russell - The Lion of Boaz Jachin and Jachin Boaz (Picador, London, 1974)

Hoban, Russell – Marzipan Pig (Jonathon Cape, London, 1986)

Hoban, Russell – cited in Meet the Authors and Illustrators – Nettell, Stephanie (Scholastic, London, 1994)

Hoban, Russell – The Mouse and his Child (Puffin, London, 1976)

Hoban, Russell - Pilgermann (Jonathon Cape, London, 1983)

Hoban, Russell – Riddley Walker (Jonathon Cape, London, 1980)

Hoban, Russell - Thoughts on a shirtless cyclist, Robin Hood, Johann Sebastian Bach, and one or two other things - Children’s Literature in Education Volume 4 (Ward Lock Educational, London, 1974)

Hoban, Russell – The Trokeville Way (Jonathon Cape, London, 1996)

Hoban, Russell – Turtle Diary (Picador, London, 1977)

Tutuola, Amos - ‘The Complete Gentleman’ taken from The Palm Wine Drinkard (Grove Press, New York, 1984)

Wilde, Oscar – A House of Pomegranates (Puffin, London, 1962)

Films –

The Black Dog (UK, 1987)

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (USA/Mexico, 1974)

The Extraordinary Adventures of the Mouse and his Child (USA, 1977)

The Leopard (Italy, 1963)

Three Colours White (Poland/France, 1993))

Turtle Diary (UK, 1985)

- Webmaster note: Many thanks to James Carter for the kind and exclusive submission of this wonderful piece to russellhoban.org.

- Log in to post comments